The Wongs are gathered at Ma’s for a new year luncheon, the first time in many years. This sets off a long, suffocating conversation around the table. As the luncheon unveils torn relations and releases long-suppressed emotions, Yee, the youngest daughter, tries to come to terms with herself.

Audio excerpt

It was stuffy in the house, though it was a fairly chilly day. Moisture clung onto every inch of my skin. My armpits were drenched in sweat and my hair plastered down to my nape. I was wiping the flower pot dry when the doorbell rang.

I couldn’t remember the last time that Ma’s home was this crowded. We used to gather at Ma’s every year on the Second Day of Lunar New Year. At some point, we began having the annual luncheon in restaurants instead. Nobody had been particularly enthusiastic about it after all, except for children who looked forward to receiving red envelopes. After Father had moved into an elderly home, a wordless consensus, we stopped gathering altogether.

The morning of February 17th was humid. The daffodils sat atop the bay window, coming into bloom. This was a sign of prosperity and good luck. I used to hate having daffodils at home because the water in the pot smelt like mud and dirt, but I thought they were decent now. Sometimes I would take care of them for Ma. I would gently lift the bubs away from water, letting the two-day-old water go down the drain. Then I would pour fresh water into the pot until the roots of the daffodils were fully submerged.

“You’re early,” I opened the door for my elder brother Ming and his wife Lan.

“It’s been a while since I last saw Ma, can’t wait to see how she’s doing,” Lan laughed dryly. She stepped inside without looking at me. I wouldn’t call four years a “while”, but. Ming exchanged a small smile with me and closed the door behind him.

My eyes lost focus. I realised Ming and Father looked very much alike. Father had the same thick eyebrows and protruding eyes, except Ming’s were quiet and soft-spoken. They were of the same build. Father looked more dapper, he was clad in crisp shirts and pleated trousers all the time. He had sported a neat left side part until his hair got too thin. In the photo hung up on the wall in the dining room, the one where he was with Mao Zedong back in their early twenties, he radiated confidence.

Lan hurried to the sofa and grabbed Ma’s hand with both of hers before plopping down. “Ma how have you been? I have missed you a lot,” her smile was broad, her cheery voice filed a sliver out of the air. “Are you warm enough? It’s getting colder these days so remember to bundle up.” Her coo flicked through the layers Ma was wearing.

The corners of her mouth were pinned in place. “I actually bought you a new coat and I’m sure you’ll love it.” Words spewed out in the metallic shrill of an old rotary dial telephone. Ma had a small smile. “Ming could you hand me the jacket, please? Thank you. Now let’s try it on. Ma it suits you so well! Do you like the colour? It’s a little pricey but it’s sure worth it. What do you think, Yee?” Her earnest eyes sent feathery tickles down my spine.

I smiled and went into the kitchen to check whether the congee was ready. Nora, the maid, asked me to keep an eye on the stove for a moment. She had to clean Fa’s litter box. It was more suffocating in the kitchen. My palms were all clammy. When I held up my hand, I could see the pads of my fingers glistening. I rubbed my hands on my slacks to get rid of the sweat and opened the cupboard to get myself a cup for a drink. Father’s drinking glass lay within easy reach. I grabbed it and felt the graphics with the tip of my fingers. They were nearly entirely faded. I could still make out the red flower, the red sun, and the red characters Dong Fang Hong. I held the glass in my hand for a moment before placing it back at its original spot, which was marked by the ring of dust.

Growing up I feared Father. When we talked I felt that I ought to physically look up at him, hands clenched tight behind my back like a child awaiting punishment at school. He spat caustic comments in his low voice right in my face. More often in Ma’s face. The littlest things triggered the most violent outrage. Ventilation fans that had been left on, tomatoes a little too sour for his liking, soup that could use one or two pinches of salt, slightly overcooked rice which turned out a bit mushy. Things that were hardly worth mentioning at all.

I felt Fa’s tail brush against my leg. I followed her out to the living room and sat down across Ming, who was reading the newspaper in silence. Ming’s eyes and mine met. We held eye contact, his burning grey irises piercing holes through me as he continued turning the page. The look made my stomach squinch, though I did not really know why.

I heard Shing’s raucous voice, then the doorbell rang.

“Yee! I haven’t seen you for years!” Shing said.

A tight-lipped smile came to me. “Indeed,” I said. I didn’t know what to say. I forgot how penetrating his voice was. Ling, his wife, gave my shoulders a warm squeeze. “I’m so glad that we get to celebrate this holiday that’s all about bringing our family together!” she said. The laughter you hear when nobody wants to show disagreement erupted. Ming chuckled softly, his face blank and unmoving. Lan wrapped her twiggy arms around her sister-in-law. “Ling, ah-sou!” she screeched. Ling burst into a hearty laugh and pressed into the bony embrace.

Lan asked Ling whether she liked Ma’s coat. Ling felt the fabric and pinched the collar, “that’s a good coat,” she said. Shing started to make small talk, about work and his latest habit of late night jogging. We let him talk until he was done. Fa sat in my lap. She hadn’t seen them before.

“So, Shing, how’s Huen doing? Has she graduated university?” Lan asked, petting Fa on her back from the scruff towards the tail. Fa squirmed.

“It’s her last year at uni this year. She is planning to do a postgrad degree,” Shing said.

“I can’t believe how fast time flies! I still remember she ate the coconut cream bun all the time, just like Father,’ Lan said.

“I haven’t seen her eat that in years. Father, too,” Shing said.

“He figured whipped cream was bad for him,” Lan said.

No one said anything for a while. Perhaps it felt wrong to bring up Father, or that we’re still finding a way to address him without sounding offensive.

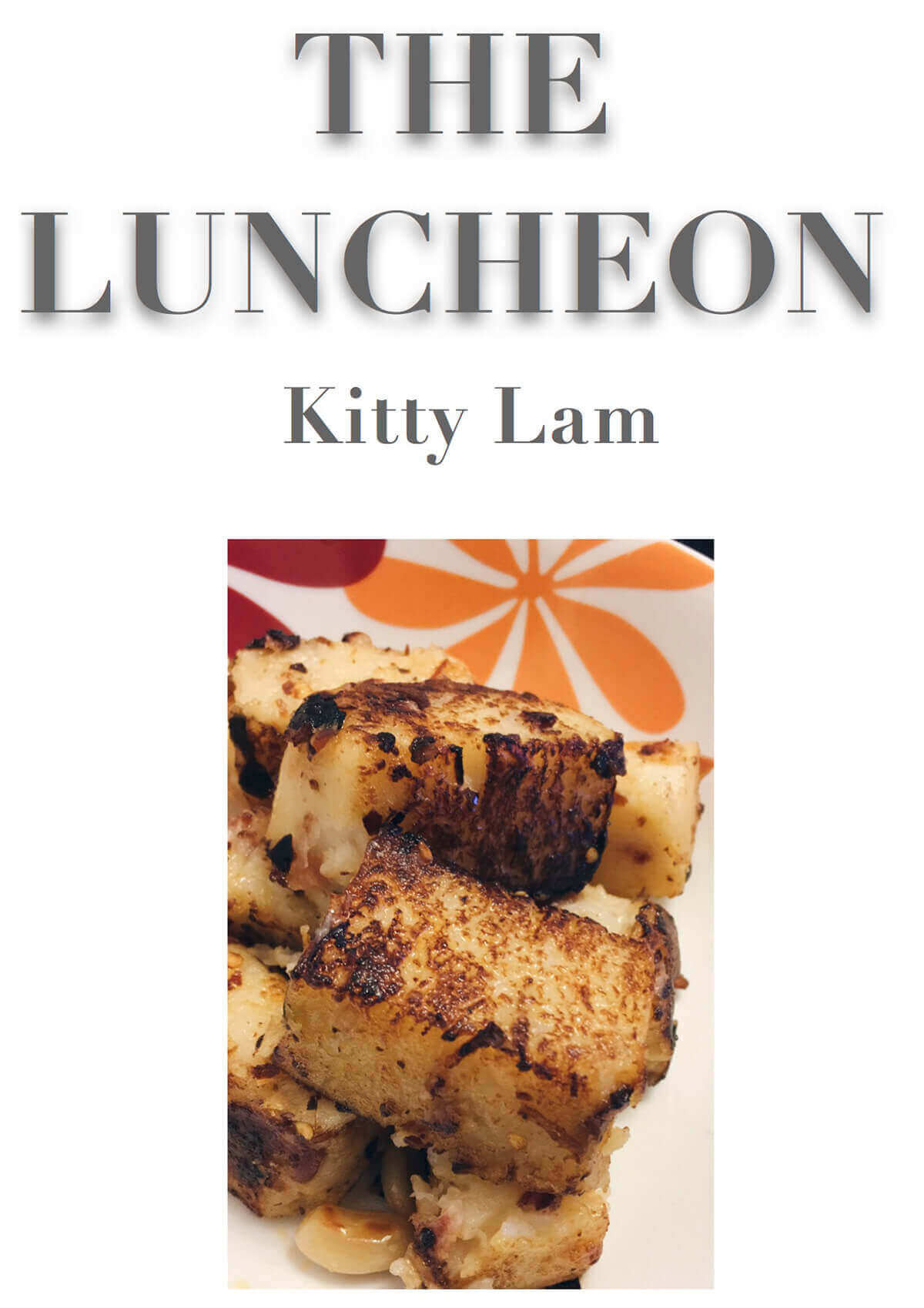

Nora came to me and told me lunch was ready. Everyone slowly stood up and went over to the dining table which I had set earlier. There were so many of us I had to dig into the kitchen cabinet for spare chopsticks. Fa got off my lap and curled up on the sofa. Nora filled our bowls with boiling hot congee. I brought rice cakes out from the kitchen. As I went back and forth to the kitchen I felt my cold, sticky feet sliding against my plastic slippers. I didn’t like that feeling. This unsettling sensation triggered the sudden onset of sweat, so there was more sweat as I took each step and I felt grime accumulating between my toes. I felt disgusting. I always loathed how damp this city was, I couldn’t stand how dampness lingered in the air even in winter.

“I don’t mean to pry, but is his stuff still here?” Shing asked, his expression unreadable.

I looked at Ming. His eyes stared intently at the paper but I could tell he was listening.

“Of course. I can’t bring myself to take care of the junk so everything is still here,” Ma said.

“That’s understandable,” Shing said.

“Can we help? Shing and Ming can give you a hand, you won’t manage to lift the bed plank,” Lan suggested.

Ma shrugged and turned her head to the daffodils. Every year we had daffodils sent to us from a friend of Father’s. It usually came with a note with New Year sayings scribbled in a Chinese ink brush. This year’s wrote Jat Tyun Wo Hei, Hap Gaa Ping Ngon. Ma tore the note in shreds and tossed it. She told me people said New Year sayings in hopes of realising our wishes, like good health and fortune, or happiness and family harmony, albeit rather unlikely. Father used to write Fai Chun every year. His penmanship was truly remarkable for a man who hadn’t received much formal schooling. Ma said he learnt Chinese through reading the newspaper.

When everyone sat down at the table, Ma proposed a toast. “For good health.” We clinked our teacups together. “Isn’t it great to eat like a family?” Ling beamed. “Absolutely,” Lan replied. Everyone laughed softly. Ling spun the Lazy Susan to help herself with some yau ja gwai chunks. I scooped up two spoonsful of spring onion for my congee.

For a while, everyone just ate. There was no chatter, just sounds of congee slurping and spoons clinking against bowls. We didn’t take long to clear the tall pot of congee, and we moved onto the rice cakes. Ma dug in right away. Her muscles were still strong enough for her to manage eating on her own. It was relieving to watch her eat, her right hand gripped the chopsticks so tightly that the turnip cake snapped into two halves and dropped back into the plate. I was the most worried about her muscular strength, regarding Father’s condition before his passing. Father’s hands always trembled as he ate, his grasp on the chopsticks was loose and it would take him a few trials before he could pick up a thin slice of pork. Thick mucus dripped from his chronic runny nose, dribbling down his philtrum, almost mingling with the food residue in his bowl. I had to feed myself with my right hand and wipe his discharge clean with my left. His mouth hung open ungracefully and his eager tongue was stuck out to lap up the meat. His once blazing eyes were extinguished, but somehow I found myself avoiding them more, because mine were full of pity and sympathy, which would trigger his self-imposed shame.

It had been a long time since all of us were packed around the table. I was not used to the lack of space between elbows. I wanted to swat Shing’s elbow out of my way. My upper arms could barely move now. I also could have used much more leg room if he hadn’t spread his legs wide apart. When we were kids, propping our elbows on the table only meant they would be hit with Father’s wooden chopsticks. Not with the tapered tips, but the blunt, leaden ends. Each smack on the elbow joint and each prickling wave of nerve impulse rebuked us for poor table manners. Being filial children, Ming and I kept our elbows to ourselves. We sat straight, held chopsticks the right way, and chewed with our mouths closed. Shing, unbothered by Father’s reprimands, did not care about table manners, or anything at all.

We stuffed our faces with turnip cakes and nin gou. The rice cakes were extra crispy on the outside, pan-fried as per Father’s instructions. If he were with us, there would be more nin gou to satisfy his sweet tooth.

“Pat Chun’s is indeed the best, provisions in Toronto Chinatown don’t sell nin gou half as good.” Shing bit into a thick slice, tearing off a glutinous mouthful, his open-mouth chewing disturbed the silence. As I heard nin gou getting jammed in the dent of his molars, he immediately slammed his chopsticks against the table, sucked in his left cheek, and tried to pick out the stickiness with the tip of his tongue.

“Turnip cakes are better, right Ma?” Lan flipped over several pieces of turnip cake in the plate, looking for a piece with the crispiest surface. She picked up the slice that had several burnt edges and laid it in Ma’s bowl. Ma preferred turnip cakes oven nin gou, for they were studded with peanut halves.

Turnip, or coi tau, was a homophone for good fortune. Our family had always been blessed with that, but it was only until recent months that I learnt Father had been receiving an allowance from the Party. The piece of information didn’t come as a shock. My eyebrows barely twitched when Ma showed me their passbook. I guess that was why they didn’t push Shing and Ming for housekeeping money. Or both of them didn’t bother to pay because they had always known. My stomach clenched at this thought.

The hot weather killed my appetite. My arm pits were very damp and sticky. Part of my blouse stuck to my back too. I chewed on the tips of the chopsticks and waited for others to finish their meal. But Ma seemed to have a good appetite today. I enjoyed watching her eat. She cut into the cake with her front teeth, chewed with her mouth open, and chomped on the thin strips of turnip. She opened and closed the chopsticks many times over, her hand going back and forth between the plate and her open mouth, catching loose peanuts bits fallen from the cakes.

Ming sat very straight and over-chewed each piece of rice cake. He held the bowl in his left hand, wrapped his fingers around the ceramic hemisphere and let the bowl foot rim perch atop the ball of his thumb. He bore an uncanny resemblance to a younger Father.

Lan stretched her scrawny arm across the table and dipped a burnt corner of turnip cake into chilli oil. When her flowy chiffon sleeves nearly touched the oily rice cakes, Ling blurted, “watch your sleeves!” She flung out her flabby arm and nipped Lan’s billowing sleeve.

Lan ohed and lifted her elbow. “Thanks Ling.”

We ate everything on the table. Ling and I stacked up the empty crockery and put everything next to the sink. Through the clang I could hear Lan calling us for a group photo. She told me to have Nora take the photo for us. My palms suddenly felt a little sweatier.

Lan dragged a mahogany chair over the hard wood floor and placed it right below Father’s picture with Mao. Ma sat and the rest of us stood behind her in a row. I stood between Ming and Shing. Ming’s fuzzy fleece jacket brushed against the back of my left hand. A stray fuzzy pilling from Shing’s jumper tickled my knuckles. It was then that I suddenly remembered how things used to be. I almost forgot there had been a time when the three of us posed for photos, standing shoulder to shoulder.

I just turned fourteen then. The Lunar New Year was just around the corner and Father purchased a Seagull twins-lens reflex camera. It was much more affordable than Lubitels and Minoltas. “It is as good as those darn Sai Dak capitalist cameras.” Father smiled smugly and felt the plasticky, bumpy black shell of his prized possession.

When the five of us returned home from a shopping trip for new year goods, Father was in an unusually cheery mood. “Shing, Ming, and Yee, stay in front of the door. Pose for me.”

The three of us squeezed together in front of a wall, right below where the photograph hung. “What kind of pose would you like, Father?” I scrunched up my nose. We reeked of our new jackets’ plasticky stench.

“Let’s do this.” Shing put his hands on his hips, elbows out, standing with his feet shoulder-width apart. Ming did the same. “Or we could put our hands in our pockets.” Shing suggested, changing his posture. Ming shoved his hands into the pockets of his new grey jacket.

I stuck my fists into the pockets too. We were in matching cotton-padded jackets purchased from Yue Hwa. We looked very Chinese from head to toe, and even Father’s camera was manufactured in Shanghai.

“On the count of three, flash a big smile,” Father said. His right eye was looking at us through the viewfinder. I flashed a big smile at the googly lenses.

“Are we done yet?” Shing mumbled whilst keeping the grin on his face, “my cheeks are hurting.” Ming slightly adjusted the position of his arm, I felt the rough fabric of his sleeves brush against the back of my hand. My cheeks began hurting as well, but Father put down his camera right before I felt my cheeks were going to tear apart.

“I can’t wait to see the photo!” Shing let out a sigh of relief, his chest heaving.

“Shing, stay there and take another photo with Yee. Just the two of you.” Father looked up from his camera. Ming walked off, Shing and I stood closer.

Father told us to get ready. Shing pursed his mouth in a smirk and held up a V sign. I did the same pose with my left hand and kept a broad grin on my face, despite the jacket. I hated it not only because of the cheap plastic smell, but its despicable colour. Ma picked mine out for me. It was in glowing fuchsia whilst Shing’s and was in a subdued blue-grey. We must look like a Colleen two-sided colouring pencil when we were standing beside each other. But I was glad that the photos were monochrome, it would wipe out the horrid pink and paint my jacket light grey instead.

When my left hand held still for the long exposure time, my right hand stroked the smooth linings of the jacket discreetly, the index finger following the stitched seams of the diamond pattern. I was doing the same thing right now, years later. I was suddenly aware of this habit of mine, an unconscious gesture of feeling the insides of any clothing. I usually ran my fingers along the bottom hem of my top, smoothing out tiny wrinkles on the raw edge or following the zig-zag pattern of the double needle stitch.

The camera shutter clacked once. “Do a few more,” Lan said. A few more clacks went off.

Fa was still on the sofa. She sat with her paws tucked under her body like a bread loaf. I walked over and took the seat next to her. She barely looked at me and hopped onto the bay window. She laid stretched out on her sides and licked the matted fur between the paw pads. Ming sank back into the armchair that belonged to Father and picked up the newspapers. Lan and Shing walked Ma into her bedroom and asked her about Father’s belongings. Shing said he could call up a friend and get rid of the items of little worth. Lan said they should haul up the bed plank now. They asked about Father’s pension. They talked of things in a detached manner that shot chills into the pit of my stomach. I waited in vain to hear Ma’s voice go up several decibels, crying and asking them to stop. But she only stooped and complied. I heard Shing’s roaring laughter when he spoke on the telephone with one of his pals. His voice giddy but urgent. My chest tightened. I imagined Ma fish the passbook from her bedside drawer. I could see Shing’s finger trace each digit of the closing balance. I could hear Lan soundlessly mouth the numbers to herself. Then the knot untied itself in a moments. My palms were completely dry.

“We should resume the new year luncheon.” Ling said. She patted Fa on the back.

I smiled. “Maybe not.

Fa, whose tail occasionally brushed against the leaves, stretched her forelimbs and yawned deeply. She looked up at me, blinked lazily, and shut her lids. I unconsciously let my eye muscles relax for a moment. The daffodils looked like a blinding white blob altogether, as warm wintry sunlight leaked in through the slats of the half open venetian blinds. Shafts of golden rays dripped onto the daffodils and shone through the dainty petals. The translucent thins looked delicate and extremely fragile. I shut my lids. I touched a petal. Water droplets lingering on the green leaves wet my finger. I could see exceptionally bright yellow centres and the white petals behind them. I really could.