Autobiography of My Boyfriend Jeremy

I wandered lonely as a cloud but there were no daffodils.

In this part of the city, raincoats and muggers, corners and dive bars, you’d keep your head under the hood, hands in your pockets. Not just to avoid eye contact with a scally crossing the street, but if there were four of them, one on each side of your peripheral, two at twelve o’clock, you’d be lucky if they robbed you. You wouldn’t run, not yet, you would walk towards them. Head down, eyes locked to your feet, one hand with a credit card, and the other clenching your keys. If they were to strike, go straight for the neck. Then, you’d run.

Manchester can also be a city of jerseys screaming City or United, student with attitudes, and Oasis singing don’t look back in anger. A few weeks ago, I was arrested for driving without a license. It was a rainy afternoon and I was speeding at such a rate my tyres had failed to maintain their friction on the road. The moment I realised I lost control, was a second too late before I sped into a tree and flipped a one-eighty. After towing it home, I was handcuffed in front of my parents, stripped of shoelaces, and shoved into a cell with the other bloke who stole motorbikes. He taught me how. When I was released, dad told me to get some sleep, you had a long day. They didn’t press charges and knew not to reprimand me, they were too smart. Punishment only cemented my hate for authorities, lenience made me incredibly guilty.

My parents met at Oxford University. A natural beauty of dark hair and cherry cheeks met a man with eyes of St. Patrick’s blue and modest upbringing. They were two peas in a pod. Dad became the youngest professor in Britain, with a hundred-and-ten publications, and mum, a triple honour in French, Latin, and Russian. To this day, my parents picks flowers from public gardens, a token for their ever-growing love, and dad writers poems while mum cries to letters that spell you still take my breath away. As a child, dad was a wizard of potions. He had jars labeled with familiar letters of foreign sounds, a book with spells written in diminishing size, and a table of ingredients, which I believed, created the elixir of life. For a while, I fulfilled their Oxbridge genes and fiddled with elements, cylinders, and bunsen burners. Back then, there were only two things worth doing in life. One, helping humanity. Two, being a scientist. The arts confused people.

If you must remember anything, stay away from extremes. Dad was right. But I became extreme. Much to Oxford’s dismay, Leeds happened. I crossed my i’s, dotted my t’s, copied all my assignments, jammed three years in three weeks, pulled a Bill Gates, and put off a twenty-thousand word dissertation to its deadline. I came first in class. Come finals, I spent more time scheming to miss it than opening textbook. A day before my exam, I opened a carton of milk and left it outside to battle the heat. The next morning, I carried it to the clinic, took a deep breath, held it, then guzzled it into my stomach. Moments after I threw up on the floor, I was bestowed a piece of paper, and on it, a scribble that said I was unfit for school. Granted, I was honest for being a terrible liar.

Once, an RAF cadet tried to recruit me. I’ve better things to do, I flaunted. We all have better things to do than what needs doing, like collecting t-shirts with random record labels, the more obscure and Japanese, the better. In other words, college was walking down the hallways in my bleached Stan Smiths, a mini-mullet, a sweatshirt zipped to the chest, its hood folded to a triangle, and some jeans purposefully ripped for the occasion. It was spending my book allowance on decks, mixers, and turntables. There’s more neural activity in our pre-motor cortices than the average joe. Laziness meant you were a neurotic. As an excuse, laziness was a blessing.

When you took the same road home every evening, rarely would you think to make a left from third street, then a right cross the bakery, and another, till you reached a homeless man’s bench. Rather, you’d consume your thoughts with the coffee you spilt on your coworker’s desk. You’d contemplate the morality of taking an early lunch break. You’d come back ranting about the asshole who spilt coffee all over his paperwork. You’d lie, and pretend you’d appreciated the curvatures of a hidden alleyway. Someone shoulders you, and you conjure up a scenario where you’d have punched him in the face and an audience would appear out of nowhere for a standing ovation. Every once in a while, your bus would miss a shift and this slight change of course would force you to spend some time in a bookstore. And like every freshly graduated college student, who faked a few CVs for some stapling job in the office, I had a thing for anything ON SALE.

The first thing you’d do, when sifting through a bundle of books, was to look for a cover that said consumerism-at-its-best. When reminded you were a social justice warrior, you’d dismiss these glossy books for some second-hand version in the adjacent hippie store. One was tainted with scribblings from a hard-pressed fella, whose career had been violated by capitalist aristocrats, whose wife had just divorced him, and whose prenup had left him living on the streets. But sometimes, there would be a book with a soldier holding a rifle, some dramatic overcast clouds hinting a thunderstorm, and in bolded red, The Quiet Soldier. I grabbed my wallet.

Two-thousand feet in the air, he jumped, but his parachute didn’t open. He had ten-seconds. At eighty miles an hour, he prayed to be dead before hitting the ground, a heart attack to overcome the pain of impact, a brain freeze to numb the fear of falling and, if none of the above, for ease, to enjoy that final glimpse of life. He believed the determinism of science. What influence would free will have to bargaining its death? Nature had seen many deaths, what made you more special to defy its gravity? I was a few meters away. When the quiet soldier plummeted to his inevitable death, his body accelerated into the ground, bounced a meter-high, then fell, lifeless, onto the grass.

A few years ago, my white-collar life was interrupted by a fine paperback copy of Adam Ballinger’s experiences in the Special Air Service. I called off work the next morning and ran. Ten miles cross-country, every day, every week. Hill-sprints, circuits, drills, a run-of-the-mill. Soldiering from one day to the next, a year flew by. I made it, not to SAS, not even selection, but pre-selection. I didn’t tell anyone.

Coming home from week one of pre-selection, I vegetated on the floor, a stem purged of its petals. People were puking. The room reeked of that bland chicken salad the other guy had stomached yesterday evening. I was sick. To weed out quitters, they pushed till we voluntarily resigned. Second week of pre-selection, I felt a snap in my legs and a downward force wrenched an impressive fall. Paralysed, I laid flagging. A month after failing pre-selection, I dawdled near a line for army recruitment. What can you offer me? I enquired, and was shown some stately photographs of fighter jets. Brushing aside its inflated peddling, I applied and they got back to me in three months. The next morning, I finally mustered enough courage to inform my parents, they were accepting. What do you say to a son who wants to go to war?

Sergeant manoeuvred around tables of suits, polished brogues, and silver platters. Chary of his steps that clicked, clacked, clicked, like a ticking bomb we all mistook as some soothing pitter-patter of a clock. February 18th 2008 was a Monday in RAF Cranwell. Reciprocating sergeant’s grin, we responded to his greetings and congratulations with like suspicion. A benign smile, that concealed years of entrenched inaugural routines, mouthed to an officer to shut the door. I will be in charge for the next six weeks, to train you from a civilian to a soldier. Nothing too advanced. If you do well, you’re on time, things will be fine. If not…, sergeant slammed his fists on the table, I’ll be a fucking grenade! Emphasis on the adjective.

For five minutes, the adjective crescendoed. Attention! Disrupting our fine dining, we trotted out into the cold. As ice cubes racked in the freezer, we stood in upright planks, three perfectly still, perfectly straight rows. What was leftover in my stomach froze to an anticipated shatter, a chill branched into my veins, and a neighbouring thump made everyone’s eyes twitch to that direction. Don’t fucking move! Sergeant pointed his finger at witnesses of the incident. I had lost track of my internal clock, but it must have been twenty minutes when an ambulance fired its siren. A cadet from Qatar had collapsed on his chin, blood marks stained the frosty ground. The UK cold wasn’t for him. Everyone knew about inauguration day, but nobody cared to mention it. Welcome to day one of officer training, four more years to go.

The next morning we were told to RISE, or, if you will, Respect, Integrity, Service, Excellence. Half past four, get up, clean. Half past five, stand up, inspection. My dignity was measured by a thin piece of wood. Sergeant aimed his ruler at a drop in the drain, all too stubborn to evaporate, then aligned it to a metal bar in the closet. The hangers were a millimetre too apart. Swiping his fingers at the least conspicuous of locations, he upbraided us of dust behind the bed or a speck of hair I overlooked from shaving. What’s that! A fly buzzed through the windows with the utmost blasé, fluttering its translucent wings, a warrior that had dominated our leftover meals. I was punished for breaking rules regarding no pets in the barracks. I lost my weekend.

Then it was Blue Letter Tuesday. It was a thin sheet of navy blue, a fragile piece that determined the hardiness of thirty weeks. We’d cut to a quarter, I could fail again. Consumed by my own results, I unfolded the letter and allowed my eyes to wander to its periphery. My eyes lingered for fear of epilepsy, then refocused — I made it to specialised training. My euphoria was fleeting, barely on par with expectations. I looked up and saw the other guy force a smile, dejected. I saw another affixed to the words, searching for greater meaning. By week four, we were a unit. And now, it was like losing a limb to see them go.

Buglous. They misspelt my name, and it stuck. Is buggy flying today? Not today. Today was graduation, and from the podium, I saw dad and mom from the middle to my left amongst dewy-eyed parents, with just as much courage as their children onstage — the choice to live with the perpetual fear of losing whom they loved the most. As a child, I valued a firm pat on the back; as a teenager, some laughter meant he saw his youth in me. But today, dad didn’t have to do anything. A glimpse of light reflected on his cheeks. And for the rest of my life, I could never forget the moment my dad cried.

Nine of us made it to specialised training. A year later, there were two, and by the end, none. Three months before Afghanistan, I quit. We both quit. They called me a coward. Usually, my pride would overcome me, my teeth would clench, and my mouth would clutter with explanation. But I bit my tongue, they had taught me well. With every aircraft on fire, every smell of death, everyone kept calm. Two years ago, Gaz and I took our usual ride back home for the weekend. Thoughts on killing for a living? Gaz was quiet, I was too. The silence carried its weight for my remaining years in the airforce. The day I heard myself say I can’t, I won’t, was the same day I cleaned out my room. I was relieved.

What do you do with a fighter pilot certificate? You wave it at commercial airlines. A dozen of us sat side by side against a wall that separated us from the interview. A candidate bragged about his practice to compensate for his trembling knees. When he asked, I told him I was ex-military. He shrugged his shoulders and piped down. Behind the walls bore two fine-tailored suits, your standard stout with months of beer compulsions hanging over their belts, and a lady with a notepad. The walls ran bare, with a forsaken whiteboard, and beside it, a vacant desk. RAF navigator? How’s Burns doing? We spent the next ten minutes reminiscing. Very well, Sir. The interview went well.

Technically still in the airforce, I left to Adelaide to train for Cathay Pacific. In three rows of six columns, the tables were intolerably tilted. I made residence to the back seat, furthest to the right, and waited for our morning assessment. After a brief intermission, a voice detached yet resonant made everyone’s torso twist to face me. Dick! A friend whispered amongst fallen jaws. My memory had failed me. Six months ago I was asked to record an aviation exam.

Many were too keen, but most, with a chip on their shoulders, boozed, and trifled with woman equally frivolous of their dignity. They ruined me. Anything ex-military meant you were a poser chopped from the forces, with an air over those who tried harder. Attempting to explain my difference, I realised I was equally conceited to care. Nobody is a gifted soldier. The more experience you have, the less you care to express it. After all, a soldier is quiet. After all, they kill for a living. Those who halved my training bragged in reverse.

‘A lady dressed in a silky qipao, with a fondness for oriental porcelains, married a man of furrowed brows and pots of silver. Little did she anticipate his cruelty and a depth of poppy seed. Soon a boy was born into an estranged family. Fearful of the consequences, the mother eloped with the child and kept nothing that possessed the father’s memory, all but a pearl necklace, a vow to matrimony. The child was raised secretly. In high noon, a ship anchored at their feet, and then the father came, to settle the child’s custody. Some may call this child Hong Kong. In 1997, Hong Kong returned to the mother’s roots. Affected by his father’s great smog and industrial prestige, he was less accepting of his asian siblings.’ So goes this story, sometimes, and again. ‘Blind of his contempt, I stood by his wide brim, mesmerised by the ocean, and on the other side, diesel and gasoline. Ten thousand miles from home and What’s-Her-Name, the bugle on the Late Victorian hill puts out the soldier’s light; off-stage, a war. Lost in transition, I empathised, or did I?’

Two Tornado GR4s met off the coast of Scotland in a thunderstorm. They were to fly in formation next to each other, five hundred miles an hour, two hundred feet above water, inverted if necessary to avoid their enemies radar. Based on fuel levels, they were to bomb their targets directly or raid their rival’s jet. Meanwhile, a simulated radio call meant they had to re-plan their whole mission to assist their allies. Except they didn’t.

When an accident happens, everything goes into lock-down. My phone rang. I’m now off-base, have you heard? My mind scrambled to list everyone on fifteenth squadron. I can’t tell you who, but I can tell you who they aren’t. Twenty-four hours after the lock-down, it was all over BBC. The next day, I unlocked the cockpit then dropped the keys. I couldn’t.

Two Tornado GR4s met off the coast of Scotland in a thunderstorm. Both lost in the clouds. One jet pulled their ejection seats, the other didn’t. Four went missing, one was found drifting at sea, dead. I was supposed to be on that aircraft. They died because I left.

There is another sky, ever serene and fair, and there is another sunshine, though it be darkness there. In dad’s greenhouse, bags of seeds with exotic names of soothing sounds hung on the walls, dancing in the light winds. Toys dad had invested for an orchard in the meadow lay warm on the floor from its recent use. My body planted against an apple tree. Plucking its fruit, I took a bite, it wasn’t so sweet. Contemplating its siblings unpicked, and the apple I gauchely misplaced, I thought, it was better that way.

At night, the stars told me a story…

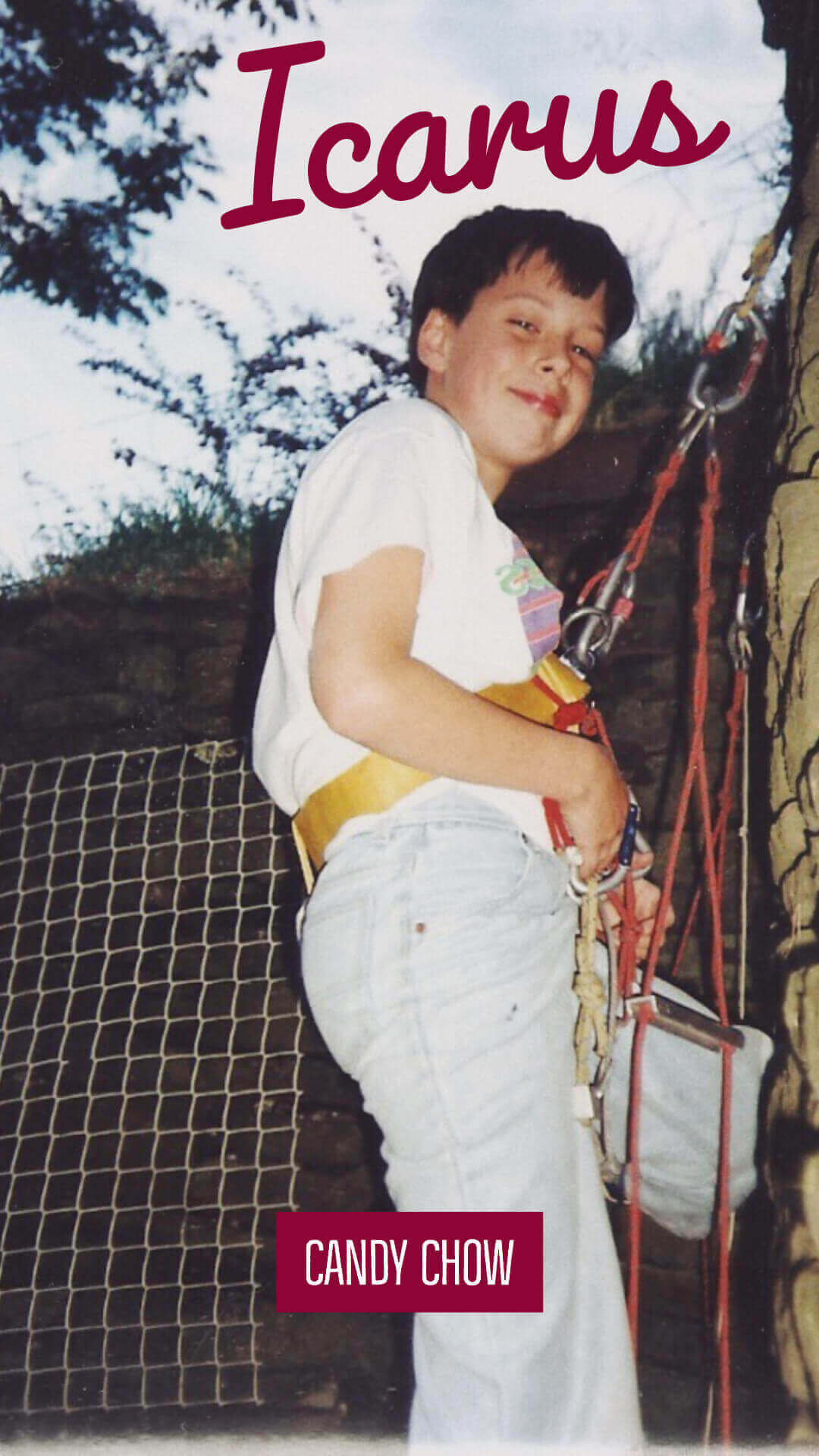

There was once a boy who dreamed to see himself above, the stars beneath. From earth he rose over higher seas, with friends who passed with similar needs. Once high above, the stars did seem to mock the state of Icarus’ wings. Don’t fly too high, or dive too low, your wings will melt, or flail in sea. He felt his wings could take, so furthered his ascent, in hubris, till his wings did break. And soon he flew with mortal arms, from the skies he tumbled into the sea. Back into the garden which bore his dreams, under the stars that saw his defeat. Then he saw what he didn’t see, the stars shining brighter beneath the trees.

…under an apple tree, when I closed my eyes and dreamed another dream.