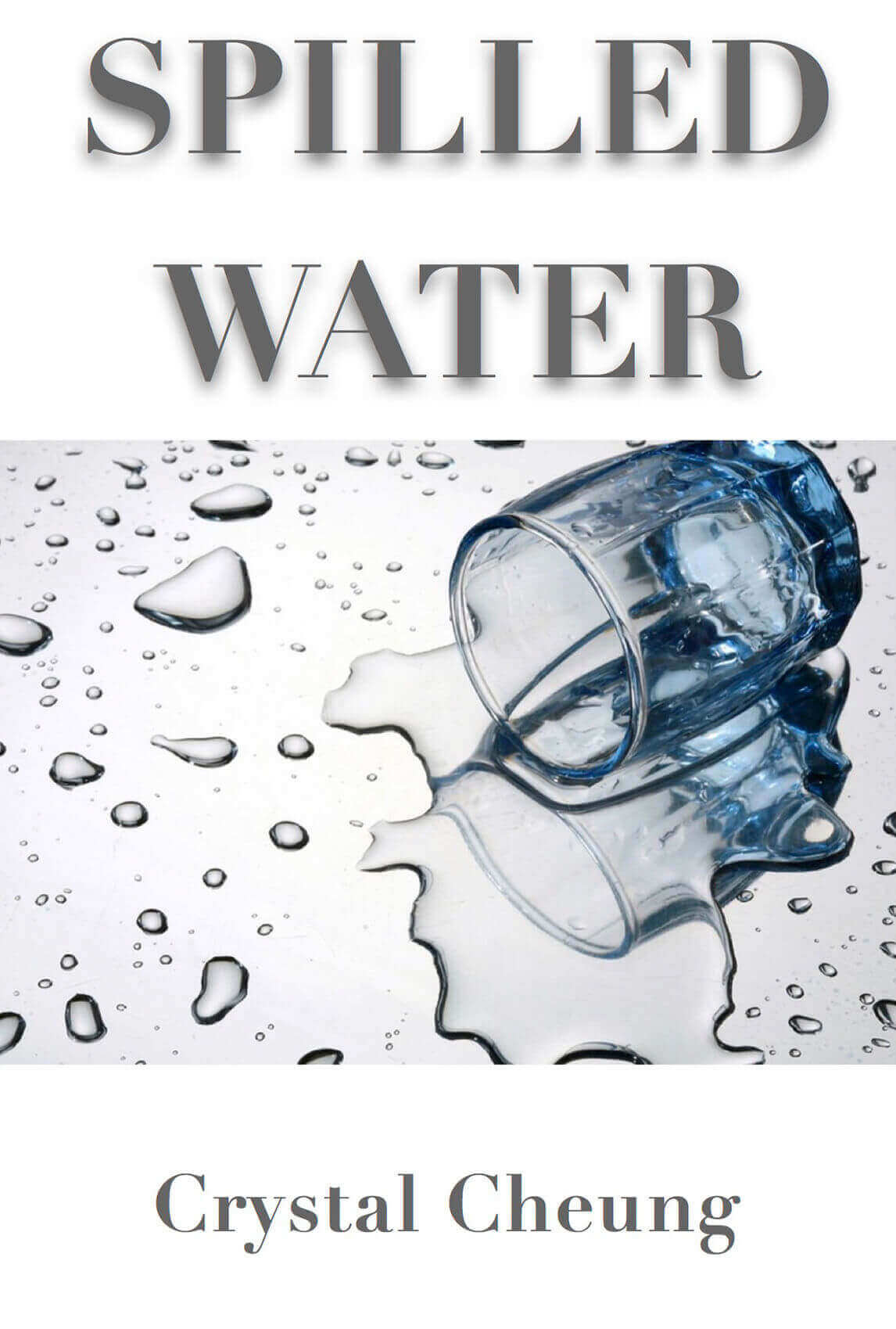

「嫁出去的女兒,潑出去的水」A Chinese idiom: ‘Married daughters are like spilled water’. Lily had wanted nothing more than her family to become complete like the ‘model,’ the traditional Confucian one taught in her textbooks. A coming-of-age story, Lily’s dream takes a turn when the grandmother justifies her attitude by comparing Lily to spilled water.

The shadows spotted my purple umbrella like big black beans. Each drop plopped onto the warm curved surface. Six o’clock. Cars navigated their way past the sodden concrete. The gutters gurgled and burped. Next to me a few pedestrians glanced at the sky, retreating under the shiny canopy of a nearby restaurant. It was new, I noted. Over the edge of the vibrant, red canopy the sky was painted with grey clouds, each a different tuft of a grey ewe’s wool.

I used to cry every time it rained. When the lightning struck the skies, threatening to slice in halves, and the quick sound of thunder followed, I used to bury myself under my covers like a rabbit in a burrow. Each time, my mother pulled the covers back and laughed at my face.

“It’s merely a storm.” She smiled.

“It’s scary.” I tried to pull the covers back from her hands.

“It’s nothing. Why, I had you in such a weather! Didn’t we, Harold?” She looked towards my father. My father nodded. “It was a storm worse than this. The wind blew till the windows flew open and the glass had to be taped. Was it the typhoon 10? It was all over the news. Another building lost over half of its windows and trees toppled like dominos.”

My mother recounted the day I was born every time it rained. Once she let slip: “He had trouble getting Grandmother here.”

The elders loved us so much, we were taught, that they spent their lives taking care of us, and we could never raise our voices in front of them in return. A Confucian belief. Etched in black ink on various white papyrus scrolls that lined the walls on Grandmother’s apartment, hanging proudly like medals, the characters, 字, moved us. That 五倫 scroll described the relationship between husband, wife, father, son – the five cardinal relationships. My crayon, ideal family, and the Chan family tree beside it.

Grandmother visited and immediately put my name on the family tree once I was born, though she later rubbed it off when Peter was born. I wailed about it, and my father suggested to put my drawing there. He had made fun of my stick figures, saying they looked the same. I crayoned Grandmother in with her walking-stick.

The largest scroll, the yellow silk bordered one on top of the sofa in the living room, said ‘fulfill your responsibilities’. Grandfather’s words. Grandfather was great at calligraphy, and all sorts of Chinese arts. Chinese painting. Tai chi. He was Chinese to the bone, or so Grandmother said. Grandfather read the newspaper on his workbench while Grandmother dusted these scrolls. She married when she was 16, my father said, and never saw her family again. She used to joke with us on our 16 birthdays that we would be considered old to marry in the past. When Grandfather passed away, Grandmother continued dusting every day till the brush marks on every stroke, making up the Chinese characters, shone.

I wanted her to be the first to know my good news. That day after school I hurried to my Grandmother’s apartment, trying to avoid the incoming storm. Strong gusts of wind played tug-of-war with my big purple umbrella, sending sogged tissues, empty aluminum cans flying. The bus was taking forever to come. I stood, glancing at my watch, staring at the raindrops that slid down the edges and pitter-pattered on the pavement, like the musicians beating drums on Chinese New Year.

“Grandmother! Grandmother!” I started yelling as soon as I opened the door and ran into the living room. I threw down my schoolbag, knocking over a little stack of books beside the couch, sending them flying over the green tiled floor. I brushed the books over and took out my letter of acceptance.

“10 gold pieces.” I heard a murmur and peered into her bedroom.

Grandmother was counting the money in her box. She must be caught up in old times. Grandmother told us how she much she had cried when my aunt was to be sold by my great-grandfather for 10 gold pieces. My great-grandfather carried her home when my aunt cried too much, but had complained for years about the loss of the money. Grandfather had said nothing.

“Grandmother!” I shouted in the room.

“What’s all the fuss?” My grandmother put the box away and waddled heavily into the living room.

I waved the letter in front of her.

“Where are your parents?” She lowered herself on the couch.

“I got accepted to the best school in Hong Kong!” I repeated.

“Stop shouting.” She waved her hand. “My ears aren’t that well.”

I stood before her. Her gaze dropped on the floor, the books sprawled out.

“What have you done?” Her voice carved a hole in my stomach.

“Those are Peter’s school exercise books.” She rose up out of her chair and stooped to pick them up. “Let go!” She clutched the exercise books, swatting my arms away as I tried to help. “You will only cause another mess. It’s no use attending a prestigious school. Girls are like spilled water. You can’t get back spilled water! Your future will be spent in another family’s home after you get married and household chores. Peter is different. He needs good education. You don’t.” Grandmother spat back. “Don’t you dare touch his books again.”

I saw the brown wooden table, the green jug, red cushions, the black inked words and the shiny white scrolls merge together in a palette of colours, swirling in the pattern of a lollipop, a spun cotton candy.

“I didn’t mean to-“

“What did you say to her?” I heard my father storming in.

Grandmother swallowed, tucking a strand of curly, silver-white hair behind her ear. The thin skin covering her jawline rippled. “I’m sick today, dear.” She sniffed and fumbled for a handkerchief, gave a little cough. The jade bracelet on her arm slid down towards her elbow, easily along her thin, bony arm, showing her protruding green veins. She patted her nose with her handkerchief before waving it in the air, as if she had to clear some dust. Her left palm remained motionless on her lap. She rolled her handkerchief into a ball, gripping it hard with her thin fingers with her right.

Her words hit me like a wooden board. Respect. I shouldn’t have barged into her home and started talking about my academics. I was so rude! I even sent my cousin’s books flying and asked my unwell Grandmother to pick them up. The Confucian values. I pressed my hands onto my face.

“Lily, pack your things and wait for me downstairs.” He was worried, like any other son. “I’ll be with you in a moment.”

I nodded and shoved my things back into the schoolbag. I stared at the ground as I walked to the corridor. It’d be better if I left.

I heard my father grumble in a low voice. Another few coughs from Grandmother. “How could you? Spilled water?”

I turned slowly.

Grandmother was facing the window, squinting and blinking multiple times. “I didn’t mean to –“. Daddy cut her off. She untucked the same strand of white curly hair and began fiddling with it, her left palm still gripping her lap. She unrolled her handkerchief and raised it, the jade bracelet sliding down to her elbow. Grandmother gave another cough. “I was just sick.”

“Daddy, she’s sick.” I ran back to Father’s side and pulled at his arm.

“Go downstairs,” he said.

I slipped on my black shoes and left. I wished he would stop blaming Grandmother. She was sick! And he had to give her such a hard time.

From then on, I was not allowed to go to Grandmother’s. It was not until I had pleaded for quite a while, along with my outstanding school results, did my parents allow it. As I passed by a bakery after school, a lovely aroma wafted in my nose. It was so sweet, one that made me want to keep sniffing, like the first time I tried on my mother’s perfume. ‘Grandmother will like this,’ I thought. It was a small bakery, and two months later I scanned the shop. Several cakes and tarts were on display, adorned with colorful fruits and huge dabs of white cream. Another case contained large, smooth buckets of ice cream, with the colors of the rainbow. I passed by the case and concentrated on the cakes. There it was, the source of the aroma. A large, pink-streaked white cake stood proudly on the top of the shelf. I glanced at the price tag. A whopping $70 a slice. Something came over me, like a wave in the sea enveloping studded shells on the sand. I handed a $100 bill to the shop assistant and was out in Jordan with a slice of strawberry cake.

“That’s a lovely slice of cake!” Grandmother said happily to me, the first time in my life.

A heated feeling spread within my body, and my fingers tingled.

“Do you want some?”

“Can I have the whole slice?”

I placed the whole cake on the table.

“Wrap it up and put it in the fridge, I’ll see to that later.” Grandmother smiled.

I started bringing all sorts of goods to her house. The best peach tart, the reddest apple, the softest cushion. Her smile kept coming. I kept bringing things there. I kept the best waffle from my breakfast for her. I used my savings to buy a pair of gloves I thought she’d like.

This would be the best present for her. A present to let her feel how smooth and slender her hands once were. I stroked her weathered, calloused hands. So many green and purple veins, protruding from the surface of her hand that used to be smooth. Her fingers were crooked with arthritis. Each bent knuckle reminded me of her efforts to provide for us. How much had she suffered for the sake of the family? I helped her put the gloves on. They were white, knitted in the finest way possible that a single stroke felt like touching the lining of clouds.

Grandmother smiled. “That’s a pair of expensive gloves.” She stroked her hands, feeling the softness.

I shook my wallet in front of her and the coins jingled. “I’ve only got a few coins left.”

Grandmother waved at me, her gloves brilliant under the lights.

I started walking towards the bus stop when thunder sounded. The clouds shrouded the clear blue sky, suffocating the streets in a dark, bitter grey. Backing into the lobby, I thought it’d be best if I borrowed an umbrella from Grandmother.

I inserted the keys and turned the lock. Spotting umbrellas on the rack, I took one carelessly before I noticed Peter, sitting in front of Grandmother in the bedroom. He hadn’t noticed me. Something flashed as he moved. An intense, uncomfortable white.

Grandmother patted his head. “My 寶貝.”

“Hmm?” Peter stared at Grandmother.

“Nothing dear.” Grandmother hugged him. “I had to suffer a lot to bear your father.”

“Suffer?” Peter rubbed his face.

“Suffer, your grandpa.” She sighed. “Your aunts were nearly sold when we were in poverty.” She took Peter on her lap and started rocking him. “But it’s all fine now. We belong to the Chan family.” Grandmother tickled Peter with bare, bony hands and both of them burst with laughter, like balloons popped at parties.

Peter was wearing white gloves. As he wriggled on Grandmother’s lap I saw a glimmer of purple that was out of place with Grandmother’s black pants. White lace peeked out from the purple, a harsh white that blended with the gloves. Underneath him was my softest cushion, the one that I had so carefully sewn for two weeks, the one that I had gifted to Grandmother a few weeks ago.

Once, I watched, as a young child, clad in uniform, dragged her feet along the puddles, stooping to kick up droplets in the air with her yellow boots. The water splashed and spilled all over the concrete, making the stones glisten like a layer of oil on the ocean, molded with impeding scorn. “There are more puddles in the front, dear,” an old lady said, drenched. She pointed to the open path of the street.

I pressed my lips again. Weights attached to me, dragging me with them. The shared blood in me, useless. I would never be her 寶貝. An aching sensation spread across my body. My legs dragged themselves on as if they weren’t mine anymore. My head ached. It was as if I was looking at a television channel that couldn’t connect properly. Everything was fuzzy, black and white. I wanted to throw both of them out of the window. To watch them writhe in pain, blood dripping slowly from their heads. Their glistening eyes begging for mercy. The thought disappeared, quick as it had come. They were family! I let myself out of the house, a lump charging in my throat. Tears welled, streamed down my cheeks and dripped on my white blouse.

The open path lit up. The child dashed forward, her grandmother hurrying to catch up, tilting the tiny black umbrella towards the child, adjusting the angle each time the wind decided to play with it. Perhaps the rain is more satisfying with a mix of tears. When everything is wet, the dampness on cheeks is unfelt. I stood in the middle of the rain, shivering in the cold afternoon air. Each cold drip dropped on my warm scalp, studding my hair like small diamonds.

Scenes flickered and replayed in front of me, as if my brain had opted out, become a videoplayer. One year ago. I compared the red packet money from Chinese New Year in Grandmother’s room secretly after dinner with those of my cousins. I had received the least from Grandmother and the most from my parents. Other stories flickered in my head. Grandmother’s stories. How Grandfather measured out the brush marks of each stroke in the Chinese characters to make sure they were even. Calligraphy was Grandfather’s treasure. The story of how water used to be only accessible through carrying them in buckets every day and Grandfather had to take care not to spill any or she could not do the dishes. Spilled water was useless.

“Gosh.” The manager from a nearby restaurant left his shop and commented at the rainwater gushing like miniature waterfalls from his shop’s shabby yellow canopy. “Look at the weight of that water.”

“That canopy’s old. The water can’t slide smoothly off,” an employee replied.

“It should be changed.” The manager shook his head at the water. “Look at that, feel so sorry for those in poverty.”

The employee watched the water spilling from the canopy and hitting the gutter with a large thud. “There’s a rainwater cycle, after all.”

I jingled my wallet and counted out the coins I had left. Just enough for a treat. I bought myself a small piece of strawberry cake. I stood closer to the bus queue, waiting as I munched on it, the layers melting in my mouth like toffee as if under a hot sun.

A tiny shaft of light lit up the streets, the late afternoon sun pushing its way from ash-grey clouds. I saw people hurrying along the streets to their next errand, their bags above their heads, to make up for the time the rain had delayed. Shiny raindrops rolled off the surface of my black school shoes and hurled themselves onto the ground like divers jumping into a swimming pool.