Biography of My Great Grandmother

Chapter 1: The Peony Hairpin

“Daddy, look what I have bought!”

“Is this how you waste my hard-earned money?”

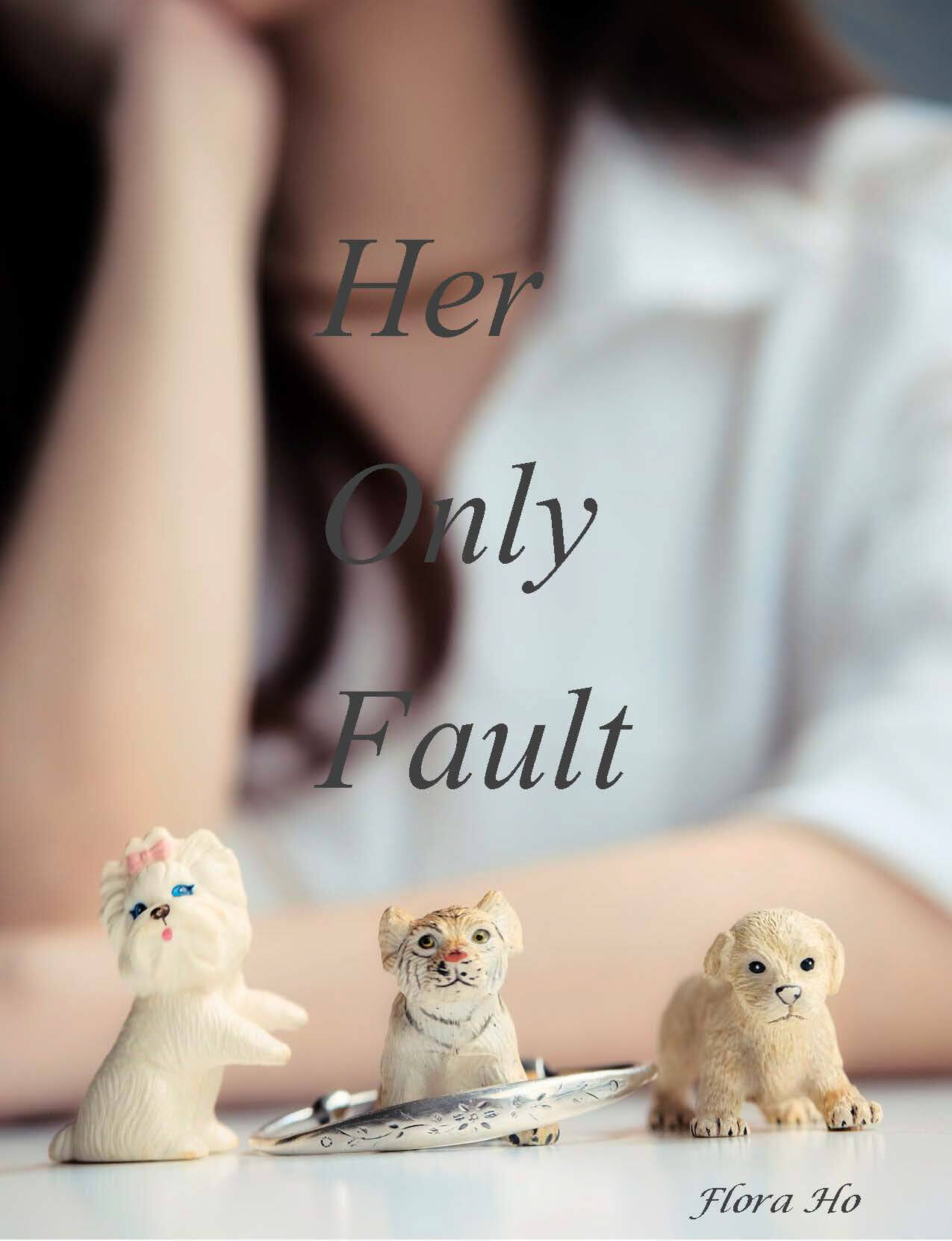

“Aiya, just have a look. They are all vintage!” I spread out across the dining table the accessories I grabbed from a newly opened thrift store in Kwun Tong as I shushed my father. He sighed and put away his newspaper on the wooden coffee table which we inherited from my mother’s eldest sister. On the table, there was a pocket watch with a rusted chain, a poster of the Beatles when they released the “Help!” album, two pairs of glass earrings, one in the shape of a rose and the other in the shape of a deer, a brown leather book cover and a hairpin in the shape of a peony.

Daddy grasped interest in the shimmering histories of each object. He always had had a thing for history and it seems he knows the history or backstory of everything. My bedtime stories consisted of all types of war stories or the life of a particular historical figure including but not limited to ancient Chinese Emperors, generals and modern days politicians and writers.

“Daddy, imagine you are pulling out the pocket watch at the office, wouldn’t that shock all of your colleagues? Oh! And the poster! We should hang it up on top of my working table so every time I study I’d look up to my life motto! And…

“Did you know almost all the songs by the Beatles were written by Lennon and McCartney? You do know who they are right? I should have told you before. And boy Lennon’s death was absolute tragic! He was shot in 1980 by a…”

“I should wear white with the rose earrings, I would look really elegant with this or maybe red…”

“What is all the fuss about?” Mom walked out of the room and interrupted us. We were conversing in totally different tracks as usual.

“We are just looking at the stuff I bought earlier today. Come and have a look!” I held up the earrings to my mother while she sat on one of the chairs at the dining table.

“Oh!” Mom exclaimed as she picked up the peony hairpin. “Honey didn’t you once tell me something about your grandmother having a hairpin like this?”

“Oh yes. But it’s gone now.”

My great grandmother had a purple crystal hairpin in the shape of a peony. In the language of flowers, peony meant prosperity and blissful felicity. The hairpin was given to her as one of the marriage gifts from my great grandfather.

My great grandmother was 16 when she worked as a maid in a prestigious family in Macau who made its prosperous fortune through the business of Chinese medicine. She served both the master and his four wives. She was as common as any other maid in the house who brought tea whenever she was told to. Little did she know, her life would end up in a tremendous change of events.

One day, typical and tedious as it was, she was raped by the master as she was cleaning his bedchamber. In my grandfather’s words, she was “flowered”, a lucky event any servant girl would have ever wished for. As a 16-year-old girl with a lack in sexual knowledge, she regarded this event as a punishment. She did not give up one tear. She was later married to him due to her pregnancy with my grandfather.

Grandfather said this incident had done her good. It was the golden opportunity that granted her the privilege to rise from a servant girl to one of the ladies in the house. She changed from serving to being served. Giving the family line one son and one daughter, she was much cosseted by my great grandfather. Her old cotton clothes were replaced with gowns and dresses made from silk with vibrant colours. Her diet changed from leftovers to carefully and delicately decorated cuisines. Her hair was regularly washed and combed every morning, tied into a high bun and flourished with a peony crystal hairpin in the shape of a peony. Now that she was a lady in the family, she could no longer call her fellows as friends. She was taught to change her disposition, demeanour and manners. The old lady, who worked in the kitchen she once politely addressed as Aunt Liu, changed to Ah Liu. Her close friend, Sister Fan, became her close servant and followed her everywhere, addressing her needs, her commands. Her only friends were her children.

Daddy said her only fault was being a woman at the wrong time in the wrong place.

This abundant life didn’t last long. My great grandfather died five years after his marriage to my great grandmother. His other wives bullied and exploited my great grandmother since my great grandfather’s death. Lacking in a strong family background and abundance in the bank, she was a natural target for the exhibition of class hierarchy. The family never liked her. For a woman who bore a son was a woman with power when the husband was alive. They envied her for her firstborn son. She was given opulent attention ever since the child was born. Not only was she a latecomer, worse, she once a servant, who served as the lowest. Standing tall among the rest of the wives was an outrage. Yet what could they do, when she was a mother of two, and most importantly a mother with a son?

Now that she became a widow, her children who wore the same family name as their father were bereaved of the family name. Their luxury, comfort and glory went along with their family name. My great grandmother and her children were gradually deprived of materials and later daily necessities. Those who secretly brought her food and water were openly beaten in the garden, with the rest of the family as the applauding audience. It didn’t come as a surprise when the three were “asked” to leave the house. “Unfitting” and “unauthentic,” they called her, my great grandmother took her old cotton clothes and shoes and decided to bring my grandfather and his sister to Hong Kong. As my grandfather recollects, she pulled the peony hairpin from her bun and smashed it into pieces on the ground at the front door before she left.

Chapter 2: The Dog Statue

With a bag of old clothes, and two children, ages 11 and 9, my great grandmother arrived in Hong Kong in early 193,9 where she found two things, a squatter hut in upper Central and a job as a cleaning lady. To my grandfather and grandaunt, their condition was absolutely appalling. Coming from a grand mansion of 2 blocks, each with 3 floors and a garden of 10,000 feet, the three started a new life in a squatter hut of less than 150 feet.

“The entire house was smaller than the toilet in Macau!” Daddy laughed.

My great grandmother and her children shared one kitchen, one bedroom and one living room with the Laus, a family of 5. While it was considered a luxury for my great grandmother to share a bedroom with her two children, the entire Lau family slept in the living room. They barely owned any furniture. After all, what could you possibly fit into a house like that? They did own a folding table for eating and a few bamboo mats for sleeping.

“Your grandfather would spend hours and hours glorifying the bamboo mats when I was small. They keep the floor clean, they don’t trap heat, they keep you feeling cool and they are washable blah blah blah. He still keeps one at his home, I think. It’s his favorite furniture and perhaps it makes him nostalgic for the old days.”

While grandfather’s memory of the hut stays fond with the bamboo mat, one of my grandaunt’s worst nightmares evolved around the public restroom where the entire floor shared two cubicles. Not only were they extremely foul, they were often hot beds of theft, rape and drug abuse. Whenever grandaunt went to the toilet, she was always accompanied by my grandfather and the male neighbours. The idea of privacy never came in mind. It’s amazing how the neighbours kept such a close relationship with each other that they are willing to act as your personal toilet guards 24/7. In fact, the conditions with the public cubicles were so extraordinarily disgusting, my grandfather and grandaunt tried throughout their entire lives to forget about the foul mess inside.

The Laus were not the best roommates imaginable. They were loud, crude and very protective of their belongings. Whenever my grandfather or grandaunt walked by the living room, they would make sure everyone in the family (and sometimes the entire floor) was aware and cautious of their every little movement. “You can’t blame them really. At times where thievery happens every five minutes, you have to be very careful. But your grandfather still hates them wholeheartedly,” Daddy says. When the family first moved in with the Laus, they took turns to wake up at night to watch over their belongings for the first few months. It wasn’t until my great grandmother paid them with 1 dollar every month as a kind of rental fee that the Laus could sleep in peace. At their times, a dollar could buy you two bowls of fishball noodles.

While the children stayed in the squatter hut, great grandmother would get up at 4 in the morning every day to pick up valuable trash on the streets such as glass bottles for selling. While the brothels in Lyndhurst Terrace were relocated to Shek Tong Tsui, new restaurants and shops took their place. Now that I think about it, my great grandmother was truly one of the pioneers of recycling work in Hong Kong. Every morning, she would collect the used bottles and tins from restaurants and shops and wash them so that she could sell them to other restaurants as if they were brand new. It’s a clever way to make money without any cost. Although she wasn’t always sufficiently persuasive, she was able to make a few cents every day. During the afternoon, it was her time to rest after the long hours of picking and washing in the mornings. She would then resume to work when night falls as she climbed up the Peak every night to clean out the trash for the rich Westerners.

There was a Scottish family who was particularly fond of great grandmother for she was quiet and efficient. On the one hand, she didn’t know the English language. On the other hand, she had always stayed quiet after her marriage to my great grandfather. She didn’t like to talk unless the situation demanded absolute necessity. Grandfather once told me the Scottish family was one of the most prestigious families in Hong Kong and owned large shares in banks. They would frequently pass old belongings to my great grandmother such as clothes, shoes, blankets and sometimes even food. The stuff which the Scottish family reckoned as garbage often proved to be crucial in my grandfather’s and grandaunt’s survival. With only a few cents of daily income, great grandmother could never have been able to provide them with sufficient food, not to mention daywear or a blanket to protect them from the cold during winters.

The Scottish family was immensely fond of dogs and they had a rough collie living in their mansion. Sadly, the dog was later killed on the streets by rat poison and in commemoration the family had a ceramic statue made. The family mourned. In a few days, they brought in another dog as a pet.

As the year passed by, the Sino-Japanese war at the North gradually spread towards the south. Fear masked over every inch of Hong Kong soil, from bottom to top. Even the ones with political power and immense fortune living in the Peak felt more anxious and threatened day by day as the news of the war never seemed to cease. Everyone became ants on a hot pan. Hong Kong had never been as united as then. Within five months, the Scottish family had arranged for the whole family to immigrate to Switzerland, leaving their enormous mansion and some “garbage” behind. Before they departed, the family left behind some more clothes, food and daily necessities for my great grandmother to pick up at night. The rough collie statue was one of them.

You know things are going terribly wrong when the Scots leave the reminiscence of their dog behind.

The Japanese invasion in Hong Kong was inevitable and the experience was, to say the least, traumatizing. As the Japanese Army attacked Pearl Harbour, they sent bombers over the skies of Hong Kong and launched a full-scale attack over the borders of Hong Kong and Guangdong at the same time. The New Territories suffered severely. While resistance forces fought at the front lines, the common people swamped into Kowloon and Hong Kong Island. But even then, they knew it was only a matter of time for Hong Kong Island to fall prey to the hands of Imperial Japan. As grandfather recalled, the sky roamed in a furious rage with heavy black smoke filling in the last particles of the atmosphere. Air fighters flew right above every citizens’ heads to drop more bombs, and houses, buildings, restaurants, roads and hills caught in the fierce wave of fire. The city noise was replaced with the sound of the air-defense siren, warning the people to stay inside air-raid shelters dug inside hills and basements and tunnels. To my great grandmother and her children, the siren was a singsong from Hell.

On 25th December 1941, the Governor of Hong Kong raised the white flag and surrendered Hong Kong to Imperial Japan after weeks of battle, murder and bombing. Hong Kong was officially handed over under the reign of Imperial Japan. My great grandmother, grandfather and grandaunt along with the entire population in Hong Kong fell under the feet of Japanese tyranny. Christmas.

Chapter 3: The Animal Toys

The Japanese took Hong Kong under full control by the end of 1941. The city dropped dead within a week. The once lively streets in Central fell into a coma. The only sound on the streets was either the public announcements glorifying the Japanese Empire or patriotic songs sung in Japanese. By that time, the people had already given up crying.

My great grandmother could only work at night. During the day, she and her children were busy hiding in what remained of the houses and corridors to avoid being captives. The squatter hut they used to live in was burnt down into ashes long ago when the Japanese soldiers first marched into Hong Kong Island. Luckily, my great grandmother was able to hide some of the valuable belongings in a secret corner near the Scottish family’s mansion. A medium sized hole behind a piece of loose brick. Before they left the burning hut, my great grandmother took the last of her jewellery and the rough collie statue, wrapped them in newspaper and hid them inside the hole. Miraculously, the statue survived while the jewellery vanished.

The day they hid the collie and jewellery inside the hole, my grandaunt insisted to keep hold of the two small animal toys no larger than the size of a palm, one in the shape of a tiger and the other in the shape of a dog. They were the only things that she held dear and she would not let them out of her sight.

When the Japanese army settled down in Hong Kong Island near Pok Fu Lam, the family searched for new hideouts to avoid being captured by the Japanese soldiers. While the three hid in the darkest and dirtiest places of all, Chinese men, however, were given a few other choices.

Option One: To be taken away into Japanese military camps as war suspects who would later be executed.

Option Two: To be workers who would clean up the executed bodies in camps and become one of them if they are in bad luck.

Option Three: To work for the Japanese soldiers and government as translators, workers or cleaners.

From one perspective, Hong Kong became a paradise, a paradise of violence for the Japanese army. Killing competitions were frequent and blatantly published in newspapers, glorifying the top killers who took pleasure in murdering and raping Chinese men and women. Every now and then, you could find photographs of men and children being tortured, beheaded and slaughtered while the soldiers were seen smiling.

After weeks of action, the Japanese soldiers realised it was too troublesome to make arrests. To make things simpler, those who resisted or offended the Japanese soldiers would easily be disembodied on the streets where their heads were nowhere close to been seen. Many times they could be found in corners of the streets where soldiers casually kick away to avoid blockage of their vehicles. You might find a complete body hanging at the fringe of the gate at the market, where wives and children found it much easier and convenient, when they collected their husbands’ or fathers’ corpses.

My great grandmother had no problem with losing a husband to the Japanese. There was no time and space to think about a dead man.

Without the support from the Scottish family or a regular income from selling used bottles, life was getting increasingly difficult. The price of rice and water grew more expensive day by day. Clean food and water were scarce as the majority went to either the Japanese army or the Resistance. My great grandmother could no longer afford cooking rice. They had to make do by eating congee and soup for months and years. My grandfather said he was always hungry when he was a child. My great grandmother couldn’t risk working hard labour in daylight. If she was taken away, her children would die within a week without question. The money from working as a garbage lady wasn’t enough to afford food for the three of them. Soon they were taking rotten vegetables, leftover chicken bones and bad meat from the dumpsters of markets and military cafeteria. They would put every edible food in a big pot and boil soup for it was quick, convenient and nutritious. My grandfather always said it’s a miracle they survived from starvation and disease.

When the scope of violence extended from physical violence to sexual violence, many Japanese soldiers did not hesitate to burst into houses, schools and markets to randomly abduct Chinese women and girls into military camps. They were extremely thorough in searching. Many women in hide were discovered and quickly removed from their family into the big camps. Healthy boys were taken as slaves while strong men were shot or cut in sight. One photograph in the newspaper shook my great grandmother to the core. The photo featured a pregnant woman whose belly was cut wide open and the formed infant was taken out and put beside her corpse. My great grandmother then made a decision. A traumatising decision that is also brave and wise.

As my grandfather and grandaunt were playing role-play with the toy animals, great grandmother shaved her head and cut her face with a dirty knife where she picked up from the market dumpster. Again, she didn’t cry a tear as she was doing it. Luckily for her, she didn’t have to look in the mirror since it was almost impossible to get one.

Self-injury in the midst of war was considered many things. For soldiers, self-injury is an act of cowardice. For my great grandmother, self-injury was an act of defence and resistance.

For some time, my grandfather and grandaunt didn’t dare to stare at her face for too long. Or they simply couldn’t bear it. They understood her decision but the sight was too terrifying for young children. She did the same for her children, only less severely. She shaved their heads and made them put mud on their faces every time they went out even when the moon was up high and the streets were consumed by complete darkness. The fear for her daughter to be taken into comfort stations as comfort women for the Japanese soldiers was too great. One rape had been more than enough for her. She wouldn’t allow the same to happen to her children, especially when girls were often the target of lust.

During the three years of Japanese occupation, the three rarely walked on the streets in broad daylight. They always studied and worked in the middle of the night. While my great grandmother cleaned the streets, the children would hide inside the garbage cart to avoid being seen. The Resistance army created underground classrooms for Chinese children to learn basic skills. Boys were taught of simple words, defence and camouflage, girls were taught to heal wounds and cook with minimal ingredients. For every corpse they found on the streets, my great grandmother would pray to the Gods and ghosts every night to blind the Japanese soldiers from discovering the underground gatherings. The darkness lasted for almost 4 years.

In 1945, the Americans dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki that deprived the Japanese military in Hong Kong. The three re-entered daylight at the dawn of resurrection on 30 August 1945. It was the only time my grandfather had ever seen my great grandmother cry. She cried her eyes out when she saw the people waving British and Chinese flags on open streets in broad daylight.

My great grandmother was 27 when that happened.

Chapter 4: The Bracelet

As Hong Kong resumed under British sovereignty, a lot of things changed. Victoria Peak was reopened to the Chinese and the economy restored swiftly with a free market accompanied by uncountable opportunities. Government and commercial buildings filled the coast line of Hong Kong Island. Parts of the University of Hong Kong were being rebuilt and students resumed daily lessons. Roads were rebuilt, factories erected high over Kowloon, and ferries swam across the Victoria Harbour daily. The population rose quickly as the government encouraged the citizens to give birth, leading to the wave of new born babies in the 50s and 60s.

Great grandmother never remarried. She stayed loyal to her deceased husband even though the relationship was absolutely wrecked. At the time, it was of utmost importance for a woman to stay virtuous and loyal to the husband.

With very little money, the three relocated to the temporary houses in the hills of Lam Tin. Great grandmother worked as cheap labour in Hong Kong. She worked in numerous factories over Kowloon side. When the business of plastic flowers flourished, she rushed to be one of the factory maids. As garment production rose to prominence and offered better money, she ran to work inside garment factories. She was underpaid. But with a little hard work and almost no time for sleeping, she successfully brought in sufficient money for the family. In replacement, my grandaunt took up the role of Mother and learnt to cook and wash. In the daytime, grandaunt and grandfather went to a public school with a proper classroom and a proper teacher, learning languages and science. At night, the two helped their mother with sewing and cutting for any unfinished or extra work. It was a difficult time. But their experience during the war had taught them to be positive in life. This life was nothing compared to the horrors during the war.

A few years passed by and the family were relocated into public housings that were built in concrete. As my grandfather and grandaunt grew as adults, great grandmother never ceased from working. She liked the idea of earning her living and she believed it was the only way for her to connect to her past, her life before 16. As a reward for her hard work, a British supervisor of the garment factory gave my great grandmother a bracelet made from real silver. She had always worn it on her left wrist as a token of hard work.

“When your mother and I got married, she gave us her bracelet as a wedding gift.”

“It wasn’t much. But she told me the bracelet was her lucky charm,” Mom cut in.

“What are these letters?” I asked as I inspect the insides of the bracelet. There were three English letters but I couldn’t figure out what they were.

“I don’t know. But I think they were the initials of the boss who gave the bracelet to your great grandmother,” Daddy said as he held the bracelet near the light. “The markings are too rusted.”

“She had held onto the bracelet for more than 20 years and she never took it off. She was 74 when she gave us the bracelet.”

“She died shortly after our wedding. She was already very ill after decades of exhaustion.”

My great grandmother is the kind of person who looks like she’s constantly in a rage but is truly kind in the heart.

She had one photograph her whole life. The only photograph she had of herself was the one on her graveyard. She looks especially tired and upset in the black and white photo. After decades of oxidation and a lack of maintenance, the corners of the photo gradually turned brownish and yellowish. Her portrait stands tall and sharp.

The scar on her face gradually healed.

But you will never fail to notice the indented line from the left of her forehead to the right of her cheek.